(Linguistic revision of the English version by Roy Pearse)

We are wandering stars. We come from far away and we are heading to the ends of the universe. There are very bright comets that spread a large tail in the sky. Their passage close to the earth makes us look up and open our inner selves. We look at them in awe. Their beauty fascinates us; their presence raises questions: who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? What is beyond what we know scientifically and by intuition?

Great comets, like those people who stand out because they are unique, serve as a mirror. That is why their radiant glow is awaited, followed and studied with passion by the great astronomers. Like a great comet, Josep Mascaró Pasarius shone with special energy and passion. His passage over the earth, with a long stride and a sure stance, was followed with attention and admiration from the very beginning by all who loved him. Now that his brilliance has disappeared from our skies, we want to know more about him, to find out about his past and to get to know better those who preceded him and those who walked with him for a long time.

His is a story full of contagious enthusiasm for life and a jealously guarded intimacy. Here is a small part of the life he led.

Origins in the Americas

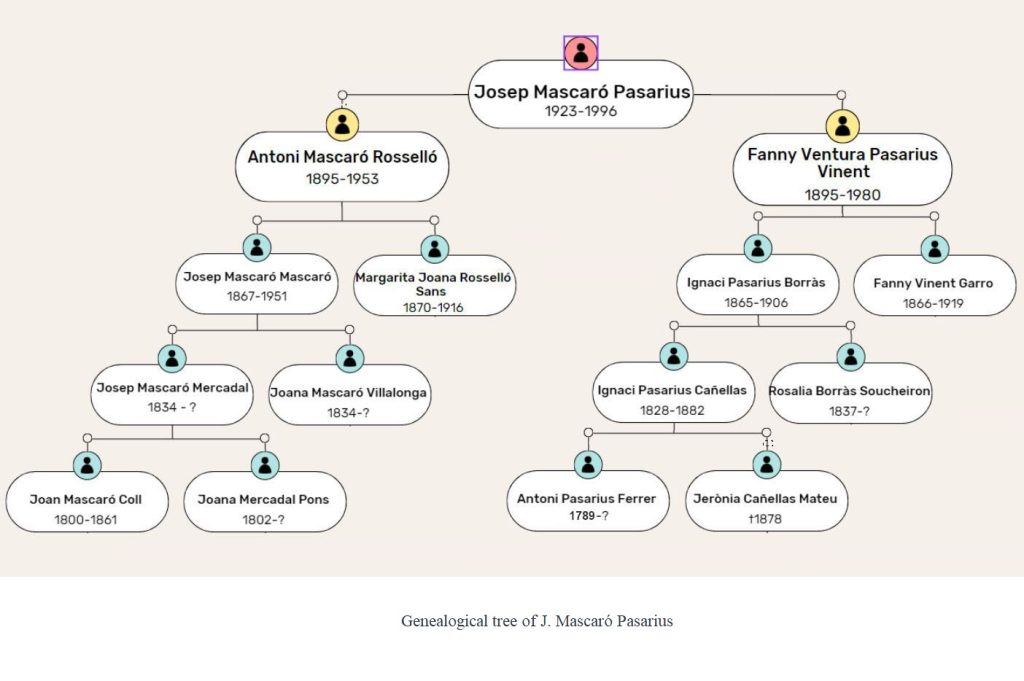

To find out about Josep Mascaró Pasarius, you first have to go back a little. His mother, Francisca (Fanny) Ventura Felipa Pasarius Vinent, was born on May 1, 1895, in the Argentine city of La Plata. Fanny Ventura’s parents were Ignacio Pasarius Borràs, born in 1865 in Barcelona, and Fanny Vinent Garro, born in Maó. The parents of Ignacio Pasarius Borràs were Ignacio Pasarius Cañellas, born in 1829 in Maó, and Rosalia Borràs, whom he married in 1862, in the church of Sant Pere, in Torredembarra (Tarragona). They had three children: Antonio Ignacio Domingo, who was born in Barcelona in 1863 and died a few hours after being baptized; Ignacio Marcos Antonio, father of Fanny Ventura, and a third son, born in 1867, who died very young and whose name we do not know.

Ignacio Pasarius Borràs studied at the school of the Jesuit fathers in Manresa, probably around 1872. His father’s family owned the store Casa Pasarius, in Maó, a city where he must have met his wife, Fanny Vinent Garro .

When Ignacio Pasarius Borràs and Fanny Vinent Garro married, they left for Argentina to start a new life, since the family did not accept their marriage, because she worked as a clerk in a store located in front of Casa Pasarius. With the money of the “llegítima” (the portion of an inheritance that must devolve to the heirs), they settled there permanently. It seems that before they left for South America they thought that they could do business there, and they took with them some samples of textiles. However, finally they concentrated on the purchase and sale of land and estates, creating a real estate company that became a prosperous business.

The couple lived in the cities of La Plata and Buenos Aires and had three children: Rosalía, born in 1891; Francisca Ventura, born in 1895; and Ignacio, born in 1899.

Fanny Ventura explained that in Argentina they lived at Calle 85 in the neighborhood of Necochea, in Mar del Plata, a port city located on the coast of the Argentine sea, in the southeast of the province of Buenos Aires. She remembered that they used to drink ‘mate’ and have some early-evening snacks at some neighbours’ houses, where they ate fried potatoes and had delicious chocolate. She also remembered that her parents loved each other very much. Sometimes they danced around their garden, very much in love. There was a fountain there and they played with the water splashing each other lovingly, while the children, Rosalía, Fanny Ventura and Ignacio, looked at them mesmerized.

The Pasarius-Vinent family lived in South America until Ignacio Pasarius Borràs died. This was before Christmas in 1910. He was buried in La Chacarita cemetery, in Buenos Aires. He was a man whom the family always remembered as happy and cheerful, whom they heard singing opera when they got up in the morning. They all really liked music. Rosalía, the eldest of the children, had learned to play a piece on the piano, In Heaven, which she wanted to perform that Christmas to surprise her parents. Unfortunately, everything went wrong. Ignacio suffered from hemorrhoids and was in a lot of discomfort. He called the doctor, but the doctor was not there. Instead of the doctor, a practitioner attended him and prescribed the wrong ointment. This poisoned his blood, and he died, at the age of 45, of acute septicemia.

The blue sea of Menorca

Fanny Vinent Garro, after the death of her husband, returned to Menorca, because her family asked her to. When they arrived in the island, Rosalía was 19, Fanny Ventura, 15, and Ignacio, 11. Fanny Ventura explained that when she arrived by boat in Menorca, she was fascinated by the blue and transparent colour of the sea water, so different from the Atlantic Ocean that she knew, and also the surprise she had when she saw that if she put the sea water in a glass, it was transparent and not blue as she saw it.

The family settled in the paternal house. Downstairs was the Casa Pasarius shop, founded by Antonio Pasarius Ferrer (born in Lleida in 1789). At the beginning of the 20th century, it was still a very prosperous shop. He had Catalan apprentices from Barcelona and Tarragona, who were going to be there for a year to learn the trade. They ate at the same table as the shop owners and slept on the counters (this type of apprentice in Catalonia was called saltataulells). One of them, Jaume Sala, married Rosalía, the elder sister.

When the godfather Buenaventura Pasarius Cañellas died, shortly after the family’s arrival in Menorca, he left his property to the only nieces and nephew he had. He left his share of the Casa Pasarius store to the heir Ignacio. And he left the property of Llimpa, located near Alaior, to his nieces Rosalía and Ventura.

Fanny Vinent Garro died on September 30, 1919. Fanny Ventura was 25 years old, Rosalía, 28 and Ignacio, 20. All the family wealth went to the son, who inherited the paternal house of Maó, the property of Binillobet, a place with plenty of irrigation near Maó, houses in Sant Lluís and a chalet on the other side of the port of Maó, in addition to other family assets.

Once her mother was no longer there, Fanny Ventura did not feel at ease in the paternal house, which now belonged to her younger brother. Ignacio was already starting to date Maria Fontirroig, daughter of Mateo Fontiroig, a well-known school teacher from Maó, and he soon married her. As a result Fanny left to live in Alaior, in the part of the property of Llimpa that belonged to her. She named it Río de la Plata. It was big and beautiful, and had a grove of pines, where they went to look for the mushrooms “ milk caps of blood” (Lactarius sanguifluus), as she used to say.

Leaving canons and rules to one side

Accustomed to life in South American lands, she was a woman with a very restless spirit. Once she was in Menorca she wanted to continue her guitar studies with a private teacher. Also, when the country folk held evening gatherings, she joined them. She played songs and sang happily with them until late. A farm worker used to hang a pig’s tail on his back and run singing «Qui me l’encendrà, el tio, tio, tio? Qui me l’encendrà, el tio de pedaç?…»(“Who will light it for me, uncle, uncle, uncle? Who’s going to light it for me, cloth uncle?…” [a popular comic song, impossible to translate]). She used to take part in local festivities, which was very unusual at that time. First, because she was a young, unmarried woman and secondly because it was considered odd that she was mixing with the local workers, whether it was when they sang, slaughtered the pig or kneaded the bread, being, as she was, the lady of the house.

She was a very beautiful and elegant woman who attracted a lot of attention among the townspeople. When she was still unmarried, she would go down, sitting side-saddle on a donkey, from the house to the village, to visit some French people who lived in Alaior. Everything about her attracted attention and made her different. She was independent, went swimming alone and used to read a lot.

At that time she met a very handsome young man from Alaior, with whom she fell in love. This was Antoni Mascaró Rosselló, who worked as a shoemaker. He was the son of Josep Mascaró Mascaró, born in Alaior, and Margalida Rosselló Sans, born in Fornells who died at the age of 46 (1870-1916). Josep Mascaró Mascaró, known as en Mascaró Gros (the Big Mascaró), was very tall (1.96 m) and well-built. He had a mill and had left-wing ideas. It is said that, because of the political leanings of those in power in the town, people were advised not to go to his mill with their corn, but everyone continued to do so, even if it was secretly, because he was a man much loved by everyone.

Antoni Mascaró, who was a shoemaker by trade, used to go to see Fanny Ventura late in the evening at the property of Río de la Plata, where she had settled. They talked through a window. He lit a candle to see better the beautiful and exotic face of that woman so different from any other in Menorca.

Wedding in Santa Eulàlia

After dating for a year, they decided to get married. Both were 27 years old. The ceremony was held on February 8, 1923, in the church of Santa Eulàlia, in Alaior. On their honeymoon they went to Barcelona. Nine months later, the first of the children, José, the protagonist of this story, was born. He came into the world “clothed” –that means surrounded by the amniotic sac- on November 13, 1923. This was a symbol of good luck. He was registered in the civil registry two days later, with the name of José Antonio Mascaró Pasarius .

The first of the houses where the couple lived, with their first child, was at Carrer de la Reina, 43 (today Carrer del Porrassar Nou), in Alaior. A long journey began that would take the family, often with few financial resources, to live in nearly 20 different houses. When Fanny Ventura was pregnant again, they moved to another larger house on the same street, where Armando was born in 1925 and, two years later, Carlos in 1927.

Fanny Ventura was an intelligent woman, very interested in scientific advances and events happening around the world. Josep Mascaró Pasarius remembered that he was once going along a dusty dirt road with his mother and she said to him: ” Not long from now a hard material will be invented to cover the roads, and the carriages will be able to travel much faster.” This shows how she had a very accurate intuition of the future arrival of asphalt, at that time still non-existent in Menorca.

Crossing the Atlantic

After living for a while in the farmhouse of Río de la Plata (Llimpa), fate would take the family to the heart of the Caribbean, to the island of Cuba. According to Perla Mascaró, her father told her mother that he was going to Cuba to make his fortune, and she replied “Then I’ll go with you». They left for the Americas in 1927 with their three sons: José, Armando and Carlos. Her mother always told her that she had something of Cuba, because she became pregnant with her in La Havana. It was very hot in Cuba, and in order for the children to sleep, they had to be constantly fanned with a large leaf hanging from the ceiling, which the mother pulled with a string. In those tropical lands they also lived through the experience of a cyclone. It was a dramatic time and she heard that they had to block up the doors and windows of the house where they lived with wood and nails to prevent the wind from blowing them away. They were there for a year. Then they decided to return to Menorca.

On their way back to Europe they stopped in New York. It was winter and the air was freezing cold. They were wearing very warm clothes, their heads covered with scarves that left only their eyes uncovered so that they were able to see their arrival at the port of New York from the deck. Josep was four years old at this time. Josep Mascaró Pasarius explained that he remembered the city of New York perfectly, with the towering skyscrapers on the island of Manhattan. He was fascinated while he looked at it and asked: “Mum, where are they going to bury so many people?”

It took them a long month to cross the Atlantic from coast to coast, by steamer. At the end of 1928 they arrived in Menorca. They settled in a house at 20 Carrer de l’Àngel, in Alaior, near aunt Joana, who made bread for the people who ordered it, and then she delivered it to the houses. Perla was born there in 1929, but this was not the last house they lived in. Shortly after, they left for Maó, to a house located near the church of Mare de Déu del Carme, where the family’s youngest child, Aurelio, was born in 1931. In this church there was a very large altarpiece, a gift from Fanny Vinent Garro, which was probably burnt or destroyed during the civil war.

Shortly afterwards, the family went to live in El Castell, on what is now Carrer Ruiz i Pablo. They rented the house from Bernat Olives Sintes, a native of Maó and father of the sisters Olives Noguera, Celeste and Victoria Juana . They weren’t there long. They returned to Alaior. They first lived in Carrer del Regaló, but soon after they returned to Río de la Plata, where they lived for two years.

At that time, Antoni Mascaró had a kind of fairground attraction, like a portable tombola, with which he went from one town to another always coinciding with the holidays, Saturdays and Sundays. The game had a round table, in the centre of which there was a kind of bell, like a cheese cover, which hid a small guinea-pig. The lid hung from a chain, which could be raised and lowered at will. Around it were compartments with bars and a hole, each of which corresponded to a card from the Spanish deck. The game consisted of allotting to the players each card in the deck for a modest price. Each player kept their card until the end. When all the cards were sold, the guinea pig was released, and when it was free, it ran to hide inside one of the doors. Whoever had the same card as the guinea pig had entered, could choose a gift, usually aluminum kitchen tools: pots, colanders, ladles, skimmers… The prizes that could be won and the props of the tombola could be varied according to what was suitable and according to the time of the year. For example, people could also win small toys for children or threads and tools for sewing, or the structure of the fair could be more complex or simple if it lasted just one day or more days. From here comes the nickname of La rata by which Antoni Mascaró and later his children were known.

At this time, the relationship between Fanny Ventura and Antoni Mascaró entered into a severe crisis, probably because of his fondness for gambling. This pastime and perhaps others too became a source of marital discord, and they decided to separate. It was during the Republic and they could divorce. This was recorded in the civil registry of Alaior on April 2, 1935. At that time the children were: José, 11 years old, Armando, 10, Carlos, 8, Perla, 5 and Aurelio, only 3 years old.

Raising five children

Mother and children left for Palma. Fanny Ventura wanted to break all ties with Menorca. Before leaving the island she decided to sell the place Río de la Plata and she appointed an agent of Alaior to make the sale, while she was away. She thought that with the money she would get, she could manage to support her family. In Mallorca they lived at Carrer del Pont, 11, in Pont d’Inca.

While they were in Mallorca, Carlos Mascaró returned to Alaior, because his aunt Joana asked him to go there to spend the festivities of Sant Llorenç, which are celebrated in the week of August 10. He left that summer. The outbreak of the civil war, with the uprising on July 18, 1936, prevented him from returning to Mallorca to rejoin his mother and his siblings. They were separated for the three years that the war lasted (1936-1939). Carlos lived with aunt Joana. Menorca was red and remained loyal to the government of the Republic. Fanny Ventura and the rest of the children were in Mallorca, which rose up with the insurgent side.

During the war they still lived in Pont d’Inca. Perla Mascaró explains that when they heard the siren warning of the arrival of red planes, they left the house and took refuge in the field under the almond trees. When they heard the bombs falling, they covered their heads and bodies with blankets. These were very hard times for them. They only had bread to eat, when there was any, and they did not have money because the trustee could not send any from Menorca. Maritime traffic between islands had stopped.

Faced with this situation, they moved to Palma. They lived in Carrer Marquès de la Font Santa, 200, near the Hostalets neighbourhood. Fanny Ventura began to work, during the day, in a factory of war material and, at night, she sewed buttons and eyelets of leggings for Casa Buades. At this time she needed all the help available. The little ones went to school and ate lunch in social canteens, because there was not enough for a single woman with children and no resources. And so the war went on.

Fanny Ventura always had a very distinguished appearance. She was a very fine lady. In the factory where she worked, she was chosen to give a bouquet of flowers to an important man who went to visit the facilities. The photo of the delivery of the bouquet was published in the Palma press. According to Perla Mascaró, the gentleman to whom she gave the bouquet of flowers put a 100 pesetas note in her hand, as a sign of gratitude, an amount that at that time was a lot of money.

At the end of the war they returned to Menorca to find Carlos. Once in Alaior, the trustee told Fanny Ventura that the money obtained from the sale of her property was no longer valid, because it was red (republican money). She always thought the trustee had cheated her. She received a small amount of money, very little compared to what the property was actually worth.

Selling the newspaper Baleares on the street

Back in Mallorca, Fanny Ventura bought a house with the money she had received. The family called it the little house of Pont d’Inca. It was located at Camí de la Cabana, 92, in Marratxí. However, at that time everything went wrong. There was no work and they had no food. The children were young. She had to maintain her family and home by herself. As an adult, Josep Mascaró Pasarius, in an article published in the Baleares newspaper, on the fiftieth anniversary of the newspaper, explained that his first job was selling Baleares on the streets of Palma. That’s how he earned his first pesetas. They probably served to help his mother.

When he was 18 years old (1942) he decided to enlist in the Legion to be able to help the family with the pay he received. He left for Africa, and went to the army camp of Dar-Riffien, in Morocco. He was there between 1942 and 1945. A short time later, Armando Mascaró would follow him. Josep Mascaró Pasarius very soon went to work at the army staff headquarters, in the Cabinet of Topography and Cartography, where he learned to draw cartographic plans for military purposes, among other things. Armando, on the other hand, entered the unit of gastadores. He paraded with the flag in front of the regiment, and also worked in the infirmary. They spent three years in the Legion. Both had a very adventurous spirit. When he was still in Africa, Josep Mascaró wrote a letter to his mother in which he told her that he wanted to travel around the world and learn about other countries and ways of life. His mother’s response, in a very convincing letter, managed to change his mind.

Valencia, land of flowers

While the two eldest sons were in the Legion, the rest of the family left for Valencia. It was post-war, a time of hunger and little work. Before leaving, Fanny Ventura sold the little house in Pont d’Inca. Perla Mascaró explains that her mother decided to set a new course in her life when she read in a book: “Valencia, the land of flowers and the sun”. Once there they settled in Calle Pius V, located near a museum, where they lived for three years. Fanny started working for Mrs. Pilar. She helped her in the house and the kitchen. It was also this lady who taught Aurelio to play the guitar, and he also learned to play the violin.

The first to return with a soldier’s license was Josep Mascaró Pasarius and shortly after Armando did so too. They met their mother and the rest of the siblings in Valencia. One started working as a plasterer and the other as a formwork carpenter.

Burning the trunk full of memories

The divorced couple, Antoni Mascaró and Fanny Ventura, were not on bad terms, and they were in touch from time to time. When they were in Valencia, Antoni asked his Fanny if their young daughter, Perla, who was then 16 years old, could go to Alaior to spend the Sant Llorenç festivities there. He also promised her that, if they returned to Menorca, he would buy a house in Ciutadella, where they could all live. That way he could also have the children close to him. All the children convinced her to accept.

The attempt to cut definitively with the past was not possible for her, because, finally, she agreed to return to Menorca. “I promised not to return, but they forced me to give up”, she said at the time. The first to arrive on the island, in 1946, were José and Perla. Since his father had not yet bought the house, they rented a few rooms at the house of Margalida Hernando Camps, married to Vicente Rocamora, who lived in a small house in Rancho Grande, in Ciutadella. When Margalida met them, she told her younger sister, Patrocinio Hernando Camps, “These people who arrived have very few pieces of furniture, but books, they have a lot.”

When Fanny Ventura finally arrived on the island, in 1947, with the rest of the children, she settled in the new house, on Carrer de la Brecha (now Carrer de la Muradeta). It was very small and had a view of the Pla de Sant Joan and the port of Ciutadella. It was in this house where the family burnt the trunk of memories, which had accompanied them from one country to another, from one city to another, always full of books and small personal items, ever since the long trip to Cuba, in 1927. The burning of that trunk, as if it were a ritual, put an end to a time of diaspora and started a new life for all of them.

At this moment, the great professional and vital journey of Josep Mascaró Pasarius begins. In Menorca there were no available maps of the island, just military maps which were for the exclusive use of the army. In 1947 he began to travel around the island by bicycle to make the maps that would eventually become, in 1951, the first Tourist Map of the island of Menorca and the Archaeological Map of Menorca. He could carry out this unpaid work by selling thread, soap and other objects to the agricultural workers of the places he visited, as well as running errands and acting as a middleman for those who requested it, with the intention of earning some money to live. In this way, he began to collect valuable information about the terrain throughout the island: he wrote down in a notebook the toponyms of the area he travelled over, took measurements to make the plans and drew all the archaeological monuments in elevation. This cartographic work was not easy to carry out. Josep Mascaró Pasarius ran into obstacles created by the military authorities who had to authorize the publication of each sheet. The maps had to go through many filters and controls, before they could finally be published. For example, Josep had to fight tenaciously to be able to write the place names in Catalan, and they forced him to name his two works Tourist Sketch and Archaeological Sketch.

Just when life was taking a new direction for all, a dramatic event would devastate the whole family and especially Fanny Ventura: the death of her youngest son, Aurelio, at the age of 16. Riding a bicycle, he collided with a cart in Carrer de la Brecha, where they lived, in Ciutadella. When he fell, he broke his leg. The young Aurelio went to live with his father in Alaior, in his aunt Joana’s home, after being operated on in Maó. Medicines and doctors were very expensive and Fanny Ventura could not afford them. Aurelio had his leg in plaster, but the plaster was not changed on the scheduled date, because the weather was bad and the doctor did not think it was appropriate to touch it. As a result of this, the leg became gangrenous and young Aurelio died in Alaior, on March 10, 1948.

Fanny Ventura would never recover from that loss, which she mourned for the rest of her life. It also motivated one of the most heartfelt poems she ever wrote, in 1978. It was dedicated to her son, A mi hijo, in which she says:

Everything tells me about you: the sea…, the flowers…,

your favourite songs

and distant anonymous voices…

that make me remember your dear voice.

The poem ends:

And there, in the infinity where you live…

I am with you!… even if you are not with me!…

With your image engraved, my heart melts

and my thoughts lie in your distant grave…

I am writing these verses…

These verses that fly by your side

formed with sobs or with prayers…

that tell you my sad longings…

and the hollow left by your memories.

Your mother

Armando Mascaró, unlike the other brothers, moved in with Aunt Joana, in Alaior, and he stayed to live there. In Alaior he met Milagros Pons Carreras, and they got married.

Carlos Mascaró did not always live in Menorca. When he grew up he left for France and settled in Toulouse, where his uncle Joan Mascaró Rosselló, his father’s brother, was already living in exile due to the civil war. There he married Colette Bardieux and became father to Jean Marc, Colette’s son from a previous marriage.

Perla Mascaró married Josep Caules Sintes, son of a well-loved family in Ciutadella, known as Cal Papa, who had a barber’s shop on Carrer de Maó, near Plaça de les Palmeres. They married and had three children: Ana Mari, Esther and José .

Fanny Ventura stayed to live with her only daughter. First, on Carrer de la Brecha and then on Carrer Qui no Passa, 6 in Ciutadella. She also spent time, sometimes a long time, at the house of her sons in Alaior, Mallorca and Toulouse. She died in Ciutadella on February 8, 1980, at the age of 84. Antoni Mascaró had died years before, on April 9, 1953, at the age of 57.

A large family

Josep Mascaró Pasarius met the person who would become his wife in Margalida Hernando’s house. Maria del Patrocinio Hernando Camps made him give up his plan to return to Valencia, as was his initial intention, once his mother and his brothers had settled permanently in Menorca.

Patrocinio, a woman with deep-set eyes, stole his heart and managed to settle down this man who had a great adventurous and enterprising spirit. The first map of Menorca, the Croquis arqueológico de la isla de Menorca, was dedicated to his mother. And to his wife, the first of the twelve sheets of the Croquis turístico de la isla de Menorca, in which he wrote: “Because without you I would never have been able to make this map”.

In Ciutadella Josep Mascaró Pasarius also met a person who would be very important in his life: Agustín Hernando Martínez de Salas, a professional photographer, who would end up being his father-in-law. Agustín went to Ciutadella to do his military service and stayed there, because he met a very beautiful girl, Àngela Camps Ribot, with whom he fell in love and whom he married when he was 25 years old. Angela was born on October 10, 1885, in Ciutadella, and was the second daughter of Josep Camps Cavaller, also a professional photographer and owner of a shoe factory in Ciutadella. Her mother was Margalida Ribot i Pons .

Agustín and Àngela lived in Carrer de la Puríssima, number 3, in Ciutadella. They had six children: Maria Auxiliadora, Rafel, Margalida, Àngela, Josefina and, finally, Maria del Patrocinio, who was born on March 11, 1928, when her parents had been married for 20 years and 10 months.

When Josep Mascaró Pasarius met Agustín Hernando, Agustín had his photography studio in Carrer de les Voltes, in Ciutadella. With him he established a relationship of friendship and deep esteem. It was Agustín who helped him in his first steps in photography, when he began taking photographs of talaiots and megalithic monuments in Menorca. The close relationship of friendship became kinship when, on June 21, 1952, Maria del Patrocinio and Josep Mascaró Pasarius got married in the church of Sant Francesc, after dating for four years. Fanny Ventura and Armando, replacing his father, who was already very ill, asked Agustín Hernando for the hand of his youngest daughter, which he happily granted, because he already loved as a son the man who would become his son-in-law.

Josep Mascaró Pasarius started making the General Map of Mallorca in 1952. For four years he went back and forth by boat between Menorca and Mallorca, always traveling on deck, the cheapest accommodation, even when it was stormy, because he now had a family to support and feed. He was staying at the Baleares guest house, in the Plaça de les Columnes. During those stays he sent bags of clothes to be washed in Menorca and did so by means of the crew of the boat that regularly connected the two islands; these clothes were returned clean to the guest house for a modest amount of money. In the same square was the wood business Maderas Sintes, run by a Menorcan man called Ramon Sintes Gelabert, who would end up being a good friend of Josep Mascaró Pasarius, because, from the beginning, he took orders that came to him by phone. This was the beginning of a small world that would soon become bigger.

During the four years of continuous travelling between Menorca and Mallorca, three daughters of Josep Mascaró Pasarius were born in Ciutadella: Maria Goretti, in 1953, Assumpta, in 1954, and Immaculada, in 1956. Finally, in January 1957 the whole family would leave to live in Mallorca. They rented a flat in Plaça de Francesc Garcia Orell, 2 (plaça de les Columnes), which would be their new and final home.

The family would soon increase. In October of that same year, Àngela Camps and her daughter Maria Auxiliadora left Menorca to live in Mallorca, after the death, due to an embolism, in Ciutadella, of Agustín Hernando Martínez de Salas. First they went to Lloseta, to the house of Margalida Hernando, and shortly afterwards to Plaça de les Columnes, in Palma. A home where the youngest daughter, Virginia, was born in 1961.

Living in Mallorca opened up new horizons for Josep Mascaró Pasarius, and his vast cultural interests could then be satisfied. On the largest of the Balearic Islands, projects from very diverse fields were born and had a long journey through time. And they led him to play, with his tireless curiosity and great divulgative drive, all the notes of a complex score, as his extensive bibliography clearly shows.

Stories always open, with the passage of time, to new plots, which grow, evolve and generate life. The four daughters grew up, married and had children, the grandchildren of Josep Mascaró Pasarius and Patrocinio Hernando: Enric, Rut, Martí, Josep, Núria, Àngela, Pau, Adrià and Joan . And then came the great-grandchildren, Josep and Martí, sons of Enric Portas Mascaró, the eldest grandson, and Júlia, Pau and Lluc, children of Àngela Cortès Mascaró, the eldest granddaughter.

And all stories have an ending: Josep Mascaró Pasarius died in Palma on May 11, 1996, at the age of 72. His wife, Patrocinio Hernando Camps, lived to be 92 years old and died on December 9, 2020. The ashes of both rest in the family tomb of his son-in-law, Gabriel Bibiloni, in the Marratxí cemetery .